Engorgement

Engorgement…hearing that word often makes me shiver. If you have ever experienced engorgement you know all too well the pain of swollen, hard breasts that feel like they are ready to burst! If you've never had it before, don’t fear we explore why engorgement occurs and what you can do about it.

Dealing with Engorgement

What is engorgement?

Engorgement is when your breasts are enlarged and sore. It is caused by a build-up of blood, milk and other fluids in the breast tissue.

Throughout pregnancy, your breasts were preparing for feeding your baby. At birth, you’ve already got colostrum ready for your baby. Colostrum is the first milk your breasts produce during pregnancy and is often referred to as ‘liquid gold’ as it is packed full of nutrients and antibodies.

As soon as the placenta is delivered after your baby is born, a hormonal change begins that reminds your body it’s time to start producing more milk. About two to six days after birth, you should notice your breasts feel fuller and your baby is swallowing more often when nursing. This is your milk ‘coming in’. If you have had a cesarean birth, it may take an extra day or so for this to happen.

How do I know when my milk has ‘come in’?

Sometime between the second and sixth day after birth you will notice your breast will feel larger, heavier and warmer. For some mothers there is little discomfort with their milk coming in whereas for many it can feel very sudden and quite painful. Resulting in hot, hard and throbbing breasts that feel as if they are going to burst!

How to recognise engorgement

Your breasts will feel full, hard and heavy and may feel warm to the touch. Your skin may seem like it’s stretched and may appear red or shiny. Tenderness and throbbing sensations in the breast are also normal during this time. Your areola itself may also feel hard or swollen and can cause your nipple to flatten - both of which may make latching more difficult for your baby. You may experience swelling or tenderness around the armpits.

Engorgement may happen on only one side, but is more common on both sides when your milk is first coming in. The fullness typically eases off after a few weeks once the supply and demand between you and your baby’s needs are established.

Along with the more plentiful milk often comes some extra swelling. Engorgement doesn’t typically last long – the initial swelling and tightness that goes along with the sudden increase in milk should start to subside after a day or so. For some mothers, it takes a little longer.

When does engorgement occur?

Engorgement is commonly a problem in the early days and weeks of breastfeeding but can also occur if your breasts are not drained well during a feed or your baby is not attaching and feeding well. You may also experience engorgement if you are producing more milk than your baby needs.

Engorgement can also happen anytime feeding patterns change, even if it’s been months since you started breastfeeding. When you return to work, if your baby starts sleeping through the night, or even if you or your baby are recovering from illness - anytime the normal nursing pattern is interrupted, you may find that your breasts become engorged. Treating engorgement quickly will help prevent plugged ducts or mastitis, common side effects of overly full breasts.

How to ease engorgement

Engorgement is not always entirely preventable but there are ways to minimise and potentially ease engorgement in those first few days as your milk comes in.

Frequent nursing should help. Try to nurse your baby as soon as possible after birth, and then aim for 10 to 12 feedings every 24 hours thereafter. Nurse your baby anytime that they are showing hunger cues, such as hand to mouth movements, sucking their fingers or tongue, or making smacking noises with their mouth.

When nursing, allow your baby to finish the first side before switching sides. Don’t switch sides after a certain number of minutes if your baby is still actively nursing. These baby-led feedings should help your supply regulate to match your baby’s needs.

Around seven to ten days after your baby’s birth, it may seem like your breasts just don’t feel as full and you may notice this again at four to six weeks after birth. This is a normal change as the swelling subsides and the milk supply evens out. You’ll still have plenty of milk for your baby as long as they nurse often and has plenty of wet and dirty nappies.

Top tips for relieving engorgement

- Breastfeed as often as your baby wants.

- Make sure your baby is positioned and attached correctly to the breast.

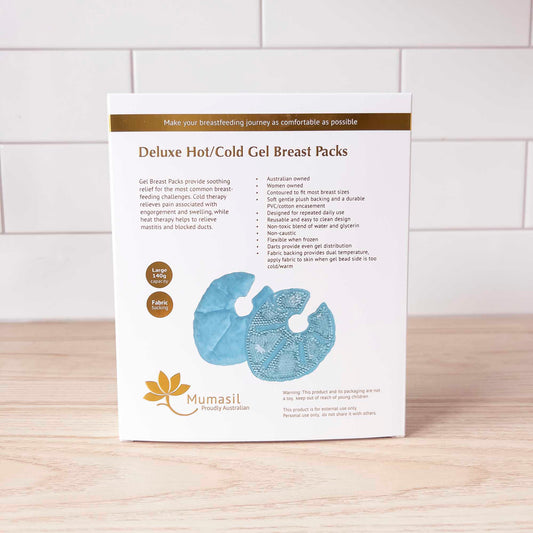

- Warm compress - Apply a warm compress prior to feeding to soften the breast and get the milk flowing. The Mumasil Warm and Cool Breast Packs are perfectly designed to conform around your breast and sit comfortably inside your maternity bra.

- Cold Compress – Apply a cool compress between feedings to relieve swelling and provide soothing relief. This can be done for 20 minutes at a time. Just freeze the Mumasil Warm and Cool Breast Packs for 1 hour before use, and always use the cover to protect your skin.

- Soften the areola with hand expression or pumping to make latching easier.

- Gently massage the breasts during feeding to get the milk moving and increase milk drainage.

- If your breasts feel overly full between feedings, express just enough milk for comfort, but not so much that your body continues to make too much milk.

You may hear that using cabbage leaves can help with engorgement – and as strange as it might sound, it’s true. Buy a head of green cabbage, wash a couple of leaves, remove the hard spines if you’d like, and place them inside your bra against your breasts. Leave them in place for about 20 minutes at a time. Repeat up to 3 times per day. Stop using the cabbage as soon as you notice the engorgement begins to subside, since overuse can lead to low milk supply.

If your baby is having trouble latching because your breasts are so full, you may need to soften the areola. Hand expression, warm compresses and pumping often help with this. But if that doesn’t work, you may want to try reverse pressure softening (RPS).

The goal of RPS is to push fluid back away from the nipple and areola. To do this, place two fingers on either side of the nipple and push gently inward while slowly counting to 50. Move the fingers to another area beside the nipple and repeat. This handout provides more information about reverse pressure softening, including diagrams for finger placement.

Occasionally, a mum has extra breast tissue in the armpit area that can also become engorged as milk supply increases. Breast tissue does normally extend toward the axilla, called the Tail of Spence. But some mums have extra glands not connected to the two main ductal networks, or may have an extra nipple, areola, or both.

With the hormonal changes of pregnancy and birth, this tissue acts just like an additional breast - meaning it may fill with milk or simply become swollen. This tissue will eventually stop growing and producing milk and should resolve without a problem. Ice packs can be helpful for comfort during this time.

Prolonged Engorgement

Prolonged engorgement may mean that your baby isn’t transferring milk properly. It also tends to happen more often when you are dealing with oversupply. Be sure your baby is positioned well and is latched deeply. You should hear swallows as your baby nurses, and your breasts should feel softer immediately after a feed.

Some mothers naturally make too much milk in the beginning of lactation, and frequent nursing following baby’s cues is the best way to tame this. If oversupply continues past the first four to six weeks, working closely with a lactation consultant can help you purposely decrease your supply (and the attendant engorgement) to a more manageable level that’s still appropriate for your baby’s needs.